Introduction: stagnant educational environment and stagnant built environment

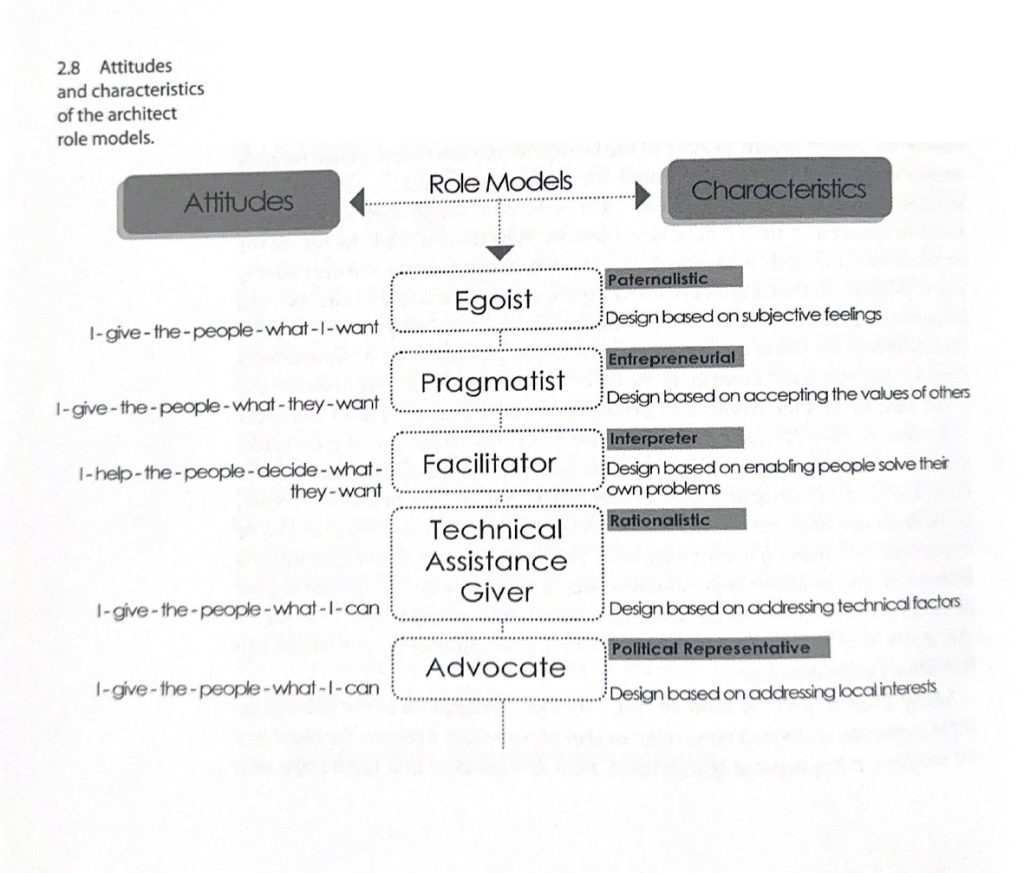

The evolving landscape of higher education in spatial design must increasingly embrace the significance of play as a transformative pedagogical tool, particularly during the formative months of academic education. This post, part of the Action Research Project (UAL: PgCert), explores the pivotal role of play in creating a democratic ground for students from diverse backgrounds, including those with various learning disabilities and neurodiversity. Drawing inspiration from the foundational concepts of the Bauhaus and Rudolf Steiner’s educational philosophies, as well as studying Ashraf Salama’s ‘Spatial Design Education’, considering Peter Burges’ model of the architect as a facilitator, and learning from Henry Sanoff with his promotion of group interactions and design games aimed at exploring community goals and spatial alternatives (Salama, 2015) the research is aiming to investigate play in creating collaborative environments both in academic and professional means.

Furthermore, the Action Research Project investigates the possibilities of integrating play in delivering tangible outcomes to improve both learning and design processes. The theoretical research in turn, is followed by an experimental workshop entitled ‘Embodying Atmospheres’ to track and observe how a drawing-based workshop, incorporating some body movement, imaginative visualization, and cognitive exercises, can bring tangible visual outcomes. The workshop aims to build a community of students engaged in activities based on shared experience of play, and in turn apply such experience onto building a industry of same inclusive environment.

Why play? Play in spatial design education.

In her book “The Magic Language of Things,” Eva Zeisel shares a gem: “To enjoy, we must learn to see,” as she opens up the chapter titled “To See: Affinitive Seeing.” It’s like an invitation to dive into the nuances of observing, reflecting, and crafting beautifully designed objects. This idea goes beyond just looking at things; it sparks a reflection on the broader world of spatial design. It’s about more than meets the eye — it’s about truly experiencing and appreciating the magic that surrounds us.

The concept of “seeing” extends beyond mere visual perception; it encapsulates and individual engagement to authentically experience and comprehend their surroundings. In spatial design higher education courses, ‘seeing’ however often is limited to seeing oneself project, as the projects often require an individual outcome. In fact, a vast majority of spatial design areas like set design, installation design, interior design and architecture to name a few, are based on either team work from the very beginning, and if not, then in further stages of delivery the involvement of a network of professionals in the project’s delivery is inevitable. For instance, even in scenarios where a spatial designer (be it set-designer or architect) is commissioned to deliver a set for fashion shoot, it requires collaboration with manufacturers, electricians, people on set.

How to break this ego-centred culture and allow people to ‘see’ beyond the self? And how to learn to ‘see’ to create not only inspiring architecture and objects, but also create environments where these creation come from?

Architecture specifically suffers from ‘dismal state of stagnation’ in architecture and design pedagogy (Salama, 2015) firstly. And such stagnation further affects the post-academic practises. Designers quite often forget they are of kind of a service to change, improve, augment the reality of practical solutions accessible to many or at least of a relatively wide range of individuals. Their creations possess the potential not only to enhance the aesthetic appeal but first and foremost to significantly impact and elevate the practical solutions available to a broad audience. Designers, in their role as agents of change, carry the responsibility to contribute positively to the lived experiences of many, ensuring that their innovations are not only visually compelling but also accessible and beneficial across a wide spectrum of individuals.

Architects’ and designer’s inclination towards self-fulfilment is often inherent in their professional ethos. While this inclination is not specifically criticised in this paper, given that architecture and design are regarded as art forms requiring visionary approach, it is crucial to understand the implications of such individual tendencies. The pursuit of self-fulfilment often contributes to the cultivation of competitive, exclusive environments, evident not only within academic surrounding but also extending into professional careers.

The current global challenges, like military conflicts, cost of living crisis, housing deficiencies, and the escalating impacts of climate change, call for a more holistic framework in addressing these issues. Especially now, fostering micro-environments characterized by a sense of community, inclusion and support become not only desired, but essential.

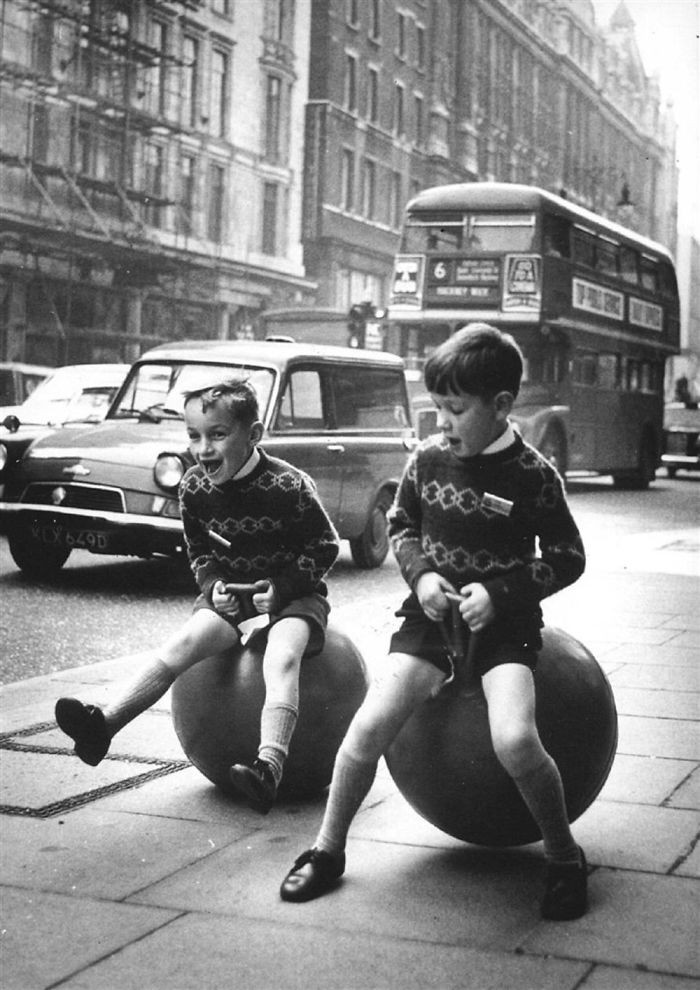

When you play, especially as a child, you spend time doing an enjoyable and/or entertaining activity.

meaning of play in English, according to Cambridge Dictionary

While looking for solution, examining play appears to be of a good path to investigate. The realms of childhood immediately associated with play not only offer a contextual backdrop for understanding the nature of play but also provides a nuanced lens through which academics can observe its dynamics and developmental significance and apply it to the adult learning. Children engage in play as a means of expressing emotions and conveying attitudes. The engagement is altruistic and non-judgemental. And learning from it, the potential programmatic play ‘must not take the form of an abstract program but must arise naturally out of the nature of the child, the evolving human being, which contains in itself the seeds of its own future’ (Steiner, 1996<)

However, the perception of play often remains underdeveloped, as its associations tend to evoke notions of childish behaviour and naivety. A comprehensive study and research would turn towards appreciation for its powerful impact not only in infants’ development, but turned towards the adults. Literature, however, seems to be lacking definition of play, potentially attributable to both the limited research on the subject (Van Vleet & Feeney, 2015).

It is also in focus to highlight the often overlooked benefits of shared memories created through playful activities. The emphasis here extends beyond the immediate connotation with collaboration, aiming to explore the positive outcomes derived from engaging in an activity and creating something individually, yet together.

Additionally, the playful experience itself is what is desired, considering it an open-ended narrative with a fixed beginning but perhaps no predetermined end. This perspective on play aligns with the paradigm of importance of creative process over outcome, a notion prevalent in spatial design higher education.

Insights derived from play experiences can shape the design of learning environments. By integrating play-based activities, educators can create engaging spaces that foster active participation, interaction, and a sense of community (Salama, 2015). From this point of view, play accordingly, appears as a mechanism for nurturing the progressive development of interaction among peers in university setting, allowing to establish and inclusive and community oriented mindset in young adults, which in future will manifest itself in creation of such environments that will facilitate further interactions.

Introducing play for spatial design throughput experimental semiotic drawing workshop – ‘Embodying Atmospheres’

The inquiry centres around the application of play to obtain tangible design outcomes, both in academic and professional environments. Play is of an open-ended narrative and it emphasises on imagination, sympathy and fun as a guiding principles. This opens up to potentially novel academic path of both teaching and learning, that integrates creativity and awareness of the surrounding environment both still and alive.

Drawing inspiration from the School of Bauhaus enriches our understanding of how inclusive play can be a catalyst for collaborative creation. Bauhaus, founded by Walter Gropius in 1919, was a revolutionary art school that sought to break down the traditional barriers between crafts, fine arts, and design. The integration of arts and crafts in the Bauhaus curriculum emphasized interactive creation — a principle that aligns seamlessly with the ethos of inclusive play (Moholy-Nagy, 1925).

Considering the natural disparities in diverse educational settings, inclusive play-based task becomes a powerful tool. Collaborative play tasks help students discover their characters and personalities. Shared joy in performing the task becomes a universal language, breaking down cultural boundaries and creating a bond that goes beyond the classroom. This mix of creativity, collaborative play, and inclusive mirrors the principles of the Bauhaus School and offers a well-rounded approach to design education applicable in both academic and professional realms.

To achieve ingenuity in this play-based task, the idea of ‘living the experience’ was incorporated too. Learning from Stanislavsky’s teaching method, the ‘Embodying Atmosphere’ workshop came up as an idea for an experimental extra-curriculum exercise.

Stanislavsky’s ‘the Method’, places a strong emphasis on emotional authenticity. Rooted in the idea of “emotional memory” and the actor’s ability to tap into their own experiences, Stanislavsky’s approach provides a framework for actors to authentically convey emotions on stage. The task prior to performing the role was to live through the experience of the character first, be it through strong visualisation or even actual experience. This method shares common ground with the concept of play, as both involve a certain level of spontaneity, imagination, and the exploration of emotions within a given context, as well as allowing oneself to be playful.

As a result a workshop was designed based on drawing implementing movement, imagination and visualisation (fig.3).

Conclusion

In conclusion, play appears to be a promising and progressive tool in nurturing creation of inclusive environments. Salama Ashraf M.’s exploration of spatial design education provides a valuable backdrop, emphasizing the importance of a holistic and adaptive approach to design education, that can be observed in principles of play. The stagnant state of architecture and design pedagogy, as highlighted by Salama (2015), necessitates a shift towards more inclusive and community-oriented practices, and that, again, seems to be possible to achieve through implementing play and play-based tasks in curriculum.

By integrating play, as inspired by the Bauhaus principles and Stanislavsky’s teaching method, into spatial design education, we unlock a transformative potential. Play becomes a vehicle for breaking free from an ego-centric culture prevalent in architecture and design, fostering a collaborative mindset. Emphasizing shared experiences and a focus on process over outcome aligns with the progressive goals of design education.

The ‘Embodying Atmospheres’ workshop serves as a practical application of these principles, bridging theoretical concepts with experiential learning. Incorporating Stanislavsky’s emphasis on emotional authenticity, the workshop enriches design education by infusing spontaneity, imagination, and the exploration of emotions. The parallel drawn with childhood play underscores the profound impact that such experiential and collaborative approaches can have on adult learning.

In essence, the integration of play into spatial design education not only addresses the current stagnation in design pedagogy but also propels the field towards a more vibrant, inclusive, and adaptive future. By fostering a mindset that values collaboration, creativity, and shared experiences, we equip emerging designers with the tools to navigate the challenges of a rapidly evolving world, contributing meaningfully to the betterment of the built environment and the communities it serves.